Apostasy

Tradition and truths

When it comes to interpreting between Islamic teachings regarding

apostasy and historical practice, change, if it is to be sustainable, comes

from within, or not at all.

By Hisham Hellyer, April 1, 2008

It

used to be that the media (whether Muslim or non-Muslim) would cover Islam in reference

to the well-known ‘three H’s’: hijab, halal and haram. It has now changed

somewhat such that the focus is on hijab, apostasy, shari’ah and hate

(preachers of). Doubtlessly from the point of view of a religion that abjures

intoxicants, this creates a rather unfortunate acronym.

On the second subject, apostasy, there has been a renewed interest, if a rather

uninformed one. In the Washington Post last year, the Mufti of Egypt, Shaykh Dr

Ali Gomma’, made his own point of view quite clear: the renunciation of Islam

has dire spiritual consequences, but not necessarily many worldly ones. When

one considers that the majority of medieval Sunni Muslim jurists (fuqaha)

have considered riddah (commonly translated as ‘apostasy’), questions do

arise. Has the Mufti, famous for his commitment to Sunni orthodoxy become

somewhat inventive? Or is the orthodox tradition (turath) of Sunni Islam

more complex than the media commonly supposes?

Catholic canon law details at least five different types of apostasy; perfidi

(when a Christian relinquishes his faith for another one); ab ordini

(when a cleric rejects the rules of the ecclesiastical life); monachatus

(when one leaves the religious life); iteratio baptismatis (the

repetition of baptism); and inobedienti (disobedience to a lawful

authority).

A majority of Muslim jurists in the medieval period (and there were a minority

of jurists who thought otherwise, which is where contemporary non-jurists such

as Dr Tariq Ramadan derive their own approach from) considered that the act of riddah

was necessarily a combination of perfidi and inobedienti. In other

words, the murtad (the one who commits riddah) did not simply reject an

internalised faith, but was assumed to be a radical bent on subverting the

established social order. On this point, there was little objection, despite

the Qur’anic exhortation that ‘la ikraha fi-l-din’ (there is no

compulsion in religion). The jurists were obviously not unaware of the Qur’anic

verse, and had no reason to ignore it. Their conception - and that of the

society around them - was that, generally speaking, the punishing of the murtad

was not ‘compulsion’, as it was necessarily bound up with other sins.

One should recall that in classical Muslim political theory, the state is

practically libertarian, and has minimal rights or responsibilities (quite the

contrary, it should be stated, to most contemporary Muslim states). It goes

against the very grain of Muslim political theory for there to be grounds for

any type of ‘Islamic Inquisition,' as the privacy and independence of the

individual is held to be paramount (sometimes, impracticably so).

As such, while the Catholic Inquisitions claimed many lives over many centuries

in practice, the punishment in Islamic law for riddah has historically

almost never been carried out. Where it has been carried out, it was generally

a façade, to cover up the 'real reason' of wanting to selfishly eliminate a

threat. One example of this was the famous case of the Sufi saint, al-Hallaj.

Another example would be the conviction of Ibn Taymiyya of apostasy, a great

irony when one considers that many of his contemporary fans (though only a

minority) are some of the most stalwart in proclaiming that all kinds of

apostasy should be punished by death.

Ibn Taymiyya’s subsequent amnesty by the political authority underlines a key

point that deserves to be explored further. While it is clear that the majority

of the jurists agreed for such issues to be kept on the books, it is equally

clear they agreed that the execution (or suspension, commutation or amnesty) of

these punishments is the absolute prerogative of the political/executive

authority in question. The political authority - and only the political

authority - had the right or the responsibility to carry out any punishment

dictated by Muslim public law. No individual could carry it out - to do so

would be a grave and terrible sin [in this, the Muslim jurists predict the

motto of the medieval Hellyer clan: pro republica sempar].

That authority could be a ‘caliphate’, a ‘sultanate’, a ‘mamlaka’

(kingdom), a democracy, or whatever happens to be the political/executive

authority of a given geographic area. Despite the obsession over terms like

‘caliphate’ in contemporary media (whether non-Muslim or not), the reality is that,

in Islamic law, the issue is whether or not Muslims have self-determination

over their own affairs. If they choose to exercise such self-determination

through calling such a state of affairs a ‘caliphate’ or a ‘democratic

republic’, it is immaterial. What matters is how the state is run. Should a

minority of Muslims still demand to have a caliphate, they have the option to

migrate to Morocco immediately, and pledge allegiance to the ruler there, who

remains the sole remaining genuine claimant to this ancient office.

The jurists also recognized the extremely strict standards of evidence and the

procedural matters required for the process of conviction (yet another reason

the punishment has not been carried out in Muslim history). However, they could

never reject them in principle. Doing so would amount to an assertion that

their legislative predecessors, including the Prophet, were collectively in

error. This does not halt the political authority from intervening even after a

successful conviction, if the authority deems carrying out such an execution

against the public interest.

The theoretical case where the medieval ruling on riddah as defined by

the majority of medieval Muslim jurists might be applied:

- When

an individual who had been Muslim subsequently left Islam

- When

someone was convicted of such by an authorised court of Islamic law (how

many of those continue to exist today?)

- When

the political authority in question judged it in the best interests of the

state and community, and implemented it (i.e., there is no room for

vigilante action)

In

the contemporary era, for a broad variety of reasons, the political authorities

of the Muslims across the Muslim world has introduced further legislation that

makes it invariably impossible to fulfil such a procedure - a right they have

under Islamic law. Such reasons include the signing of international

declarations that were to the benefit of the Muslim states, and, perhaps more

importantly, the distinction between civic and religious obligations in the modern

world. In this world, even the theoretical threat of capital punishment

pertains when the offense against God includes an offence against the community

and the state through.

Now, other muftis and authorities could argue otherwise, but they will also

point out that the implementation of any such punishment is the sole

prerogative of the political/executive authority. Eventually, it is likely that

they too will incorporate into the books of taught & applied Islamic law

that the theory itself is outdated. That would not be in contradistinction to

classical notions of Islamic law. Indeed, it has happened many times before,

and jurists have recognized as legitimate when it is in the public interest and

is the prevailing public practice.

Or, to put it in another way, it is when the maqasid (overall aims) of

Islamic law are not abrogated. Those maqasid, however, are defined not

by liberal political elites, but by contemporary specialists in Islamic law,

such as the aforementioned Mufti. Other contemporaries exist, but their

opinions hold sway among Muslims only because of their their chains of

scholarly inheritance connecting them to the Prophet himself. And therein lies

the rump - change, if it is to be sustainable, comes from within, or not at

all.

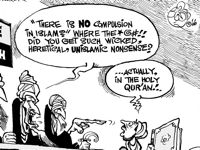

Cartoon courtesy of Khalil Bendib.

Larger version here.

Dr. Hisham A. Hellyer is Fellow of the Oxford Centre for

Islamic Studies at the University of Oxford. As founder-director of the Visionary

Consultants Group, a Muslim world-West relations consultancy,

his advice and commentary has been sought by the Home Office & Foreign

Office (UK) as well as the Brookings Institution (US) and the Washington Post

(US).

http://www.altmuslim.com/a/a/print/2695/