|

|

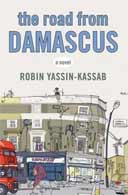

Beyond belief Robin Yassin-Kassab's ambitious debut of faith and

faithlessness, The Road From Damascus, impresses Maya Jaggi

The

Road From Damascus "Unbelief itself is a

religion", says an epigraph to this ambitious and topical debut novel. The

words of the 12th-century Sufi sage Ahmad Yasavi, coupled with a Pascal pensée

on the limitations of atheism, open a book that satirises a kind of secular

fundamentalism that can, it suggests, be as blinding as dogma. In early 21st-century Damascus,

Sami Traifi, a 31-year-old "failed academic and international

layabout" born in Britain to Syrian parents, truffles among ancestral

roots for a credible thesis for his stalled doctorate. Instead he stumbles on a

family secret, an uncle broken by 22 years in a Syrian torture jail. Back in

London, Sami's marriage to a teacher, Muntaha, crumbles as the astute, educated

daughter of a refugee from Saddam's Iraq resolves to wear a hijab. Trained

to despise religion by his late father Mustafa, an Arab nationalist supporter

of the crackdown on Syria's Muslim Brotherhood in the 1980s, Sami is already

estranged from his mother Nur, whose earlier decision to cover her hair he sees

as a betrayal of his dying father's beliefs. Secular humanism, he fears, was an

antiquated daydream shared by many modernising Arabs. "The fort had

already fallen. In its rubble a marketplace of religion had set up." Yet

for all his quoting of great poets, the simplistic nature of Sami's

understanding is signalled from the outset. Always, for him, "issues returned

to hijabs and beards". In a crisis of confusion and

self-loathing, Sami disappears on a bender, missing his father-in-law's

funeral, before a spell in the cells for possessing a spliff prompts a bout of

self-cleansing and a "trembling, contingent faith". But his own Damascene

conversion in 2001 coincides with September 11 - as we know, with heavy

dramatic irony, that it will. Once apprehended for having a rolled-up fiver in

his nose, Sami is now caught emerging from a Brick Lane mosque in a beard. With

absurd comic logic, the police conclude he has a false identity, since the

pious beardie and the coked-up dissolute cannot be one and the same. The agents

of the free world are as unable to distinguish between "Wahhabi

nihilists" and the harmlessly spiritual as between diverse forms of

political Islam. At the novel's heart are a

devastating act of betrayal in the name of secularist progress, and the family

reconciliation that comes with Sami's dawning realisation that faith is not synonymous with

backwardness, nor secularism with humanism. Muntaha, with her hijab and

prayers, proves more humane, not least in her treatment of Sami's bereft mother

- and is by far the most compelling character. Her loving correction of her

Islamist kid brother's know-nothing political posturing is among the most

touching scenes. Yet the attempt to portray a

sprawling multicultural London in the vein of White Teeth, from Nur's halal

butcher on the Harrow Road to Edgware Road's Arab cafes, is less successful.

The first-novel impulse to chuck everything in threatens to swamp the plot.

While hip-hop Islamism and a university riot over a subcontinental

anti-religious provocateur are richly germane, excursions into "reclaim

the streets" anti-globalisation demonstrations or pyramid schemes are less

so. The British-Hungarian artist Gabor Vronk, a would-be Vronsky romancing

Sami's wife, is a straw man set up to embody a predatory orientalism

("Arabs are either sensuous or violent, or both"). The novel is most

alive in its more intimate exchanges, and in glimmers of a gentle and vital

wisdom that outshines the satirical fireworks. http://books.guardian.co.uk/reviews/generalfiction/0,,2285452,00.html |

||