|

||||||||||

|

|

Quran Separated in

Variant Textual?

September 10, 2008 ·

It appears that the Christian

missionaries like to bring the already refuted topics time and again as if we

Muslims have a very short memory. The Christian missionary Jochen Katz’s recent

use of the services of Samuel Green’s article The Seven Readings of the

Qur’an is one such example. The statement of the Samuel Green

indicated with ‘>’ is the older one

and the one which is new does not contain ‘>’ after he updated the article. On 29 Oct 1998,

Jochen Katz wrote: > > The

last week Dr. Saifullah was ranting incessantly about So, it is Katz turn to start a

more incessant ranting about “Versions of the Qur’an”. Even this ranting does

not appear to solve the mess in which the New Testament is in. As we said, if

you can not fix your problems, start flaunting it. Or even better go for a wag

the dog scenario to shift the focus from the issues of your own text to someone

else’s. It turns out that this Christian

missionary was boasting about the ‘versions’ of the Qur’an sometime ago, using

the (below quoted) reference of Adrian Brockett concerning the Hafs

and Warsh transmission of the Qur’an. Unfortunately for him, it appears that he

did not learn his lessons last time. The same issue was refuted long time ago. Subsequently more material was

added to this by us. The contents of the above document are divided as follows:

So, we have essentially dealt

with all the important issues concerning the Qirâ’ât, its

isnad going back to the Companions who then took it from the Prophet(P) himself. We have also dealt with the

criteria of accepting the Qirâ’ât by the Islamic scholars as well as some very

basic examples. Inshallah, some more examples would be added in due course. It turns out that Katz is merely

trying to rehash his already refuted argument by giving it a different colour,

i.e., using Samuel Green’s work who nevertheless quotes the same references

which Katz had quoted. The principal reference used is Adrian Brockett’s “The Value of Hafs And Warsh Transmissions For The Textual

History of The Qur’an”, published in Approaches

of The History of Interpretation of The Qur’an, 1988, Edited by

Andrew Rippin, Clarendon Press, Oxford. Qirâ’ât Or ‘Variant’ We would first like to define

what is the actual meaning of Qirâ’a which is frequently translated as ‘variant

reading’. The Hans-Wehr Dictionary Of Modern

Written Arabic defines Qirâ’a as: Qirâ’a pl. -ât recitation, recital

(especially of the Koran); reading (also, e.g., of measuring instruments);

manner of recitation, punctuation and vocalization of the Koranic text.[1] It is quite clear that the Qirâ’a

is not a ‘variant’ reading or text. The Muslims in history have never

considered different Qirâ’ât as different ‘versions’ of the Qur’an.

Furthermore, neither it is defined as ‘variant’ text as some Orientalists and

Christian missionaries have done so. Keeping this in mind let us now go further

with what is written in the article. > No other

book in the world can match the Qur’an … The Well, firstly what is meant by

the phrase ‘even to a dot’? The earlier Qur’ans were written without any

dotting. Gradual efforts were made in adding the

dots and other markings to facilitate correct reading from the first century of

Hijra. If the expression ‘even to a dot’ is literally taken then one can

say that the Arabic script in Africa differs from that in the The recension of ‘Uthman has been handed down to us unaltered. So

carefully, indeed, has it been preserved, that there are no variations of

importance, - we might almost say no variations at all, - amongst the

innumerable copies of the Koran scattered throughout the vast bounds of empire

of Islam. Contending and embittered factions, taking their rise in the murder

of ‘Uthman himself within a quarter of a century from the death of Muhammad

have ever since rent the Muslim world. Yet but ONE KORAN has always been current amongst them….

There is probably in the world no other work which has remained twelve

centuries with so pure a text.[2] And guess who wrote it? The

famous Christian missionary from University of “There is probably in the

world no other work which has remained twelve centuries with so pure a text”

refutes

the status of the Bible as a pure book! Are Qirâ’ât Due To The Lack Of Vowel & Diacritical Points In The Early

Qur’ans? Samuel Green says: > … owing to

the fact that the kufic script in which the Koran was He adds further that: VOWEL

DIFFERENCES - In the Arabic script of the modern Qur’an the vowels are indicated by

small symbols above or below the basic printed letters. Again these were not

included in Uthman’s edition of the Qur’an. It is to be made clear that the

Arabic script before and during the time of cUthmân was written without vowel and diacritical

marks. To say that the vowels and diacritical marks were not included in the cUthmânic Qur’an actually shows the

ignorance of the Christian missionary Samuel Green concerning the evolution of

Arabic script. The need for vowel and diacritical marks arose only after

the time of cUthmân to

prevent the wrong recitation of the Qur’an by ignorant Arabs and non-Arabs. Arabic orthography at the time of

cUthmân was not yet developed in the

way we have known for centuries, particularly in two important areas. There was

no distinction between letters of the alphabet of similar shape and there were

no vowel marks. This may now give the impression that such a system must have

given rise to great confusion in reading. This was not actually the case

because the morphological patterns of words in Arabic enable readers to read

even very unfamiliar material without the short vowels being marked. More

important, however, as far as the Qur’an was concerned, was the fact that

learning and reading relied above all on oral transmission. In the Islamic

tradition, writing remained a secondary aid; nevertheless, to ensure correct

reading of the written texts of the Qur’an, particularly for those coming after

the first generation of Muslims, steps were taken gradually to improve the

orthography. This started with the two above mentioned areas by introducing

dots to indicate different vowels and nűnâtion and these were put in different

coloured ink from that of the text. There were also dots to distinguish between

consonants of similar shape. This work was carried out chiefly by three men:

Abű-l-Aswad al-Du’alî (d. 69 / 688), Nasr Ibn cAsim (d. 89 / 707) and Yahya Ibn Yacmur (d.129 /746). Understandably there was

some opposition at first to adding anything to the way the Qur’an was written.

Ibn cUmar (73/692) disliked the dotting; others

welcomed it, clearly because it was, in fact, doing no more than ensuring

proper reading of the Qur’an as received from the Prophet(P), and this view was accepted by the

majority of Muslims throughout the different parts of the Muslims world, from

the time of the tâbicűn. The people of Madinah were reported to have used red dots for vowels -

tanwîn, tashdîd, takhfîf, sukűn, wasl and madd and yellow dots for the

hamzas in particular. Naqt (placing dots on words in the mushaf),

became a separate subject of study with many books written on it. For details

please see the article Qur’anic

Orthography: The Written Representation Of The Recited Text Of The Qur’an. Further, the conclusions of the

missionary is that there was an … ambiguity as

to which vowels should be used. This ambiguity has lead to differences between

the vowels in the different transmissions. The aim of the Christian

missionary here is to show that prior to the introduction of the vowel and

diacritical marks, that is, throughout the period of the Prophet(P) and the Companions, as well as the

generation immediately following the Qur’an was in undetermined, fluid state, a

kind of limbo, and that it assumed concrete form only with the addition of

diacritical marks and vocalization signs, which of course was long after the

age of Revelation. In other words, for almost a century before Hijra the Qur’an

was in the fluid state and as soon as the vowels and diacritical marks were

introduced, the Qur’an started to crystallise in the form that we have now

after going through many ‘versions.’ For such a situation there is no

historical evidence. Neither, there is historical evidence that Muslims

differed over the Qur’an unlike the

Christians who differ over the extent of the canon even to this day. It

must be emphasized that for Muslims down through the centuries the consensus (ijma’)

of the community has always been a decisive proof in all matters; and as the

community is agreed that man has not contributed a whit to the Qur’an, the

matter may be considered settled. This is precisely the point which has been

noted in the quote of N J Dawood used by the missionary. It is quite clear that

all the Qirâ’ât are given equal authority. The above quote taken from N J

Dawood’s translation of the Qur’an is actually in direct contradiction of what

Samuel Green had intended to show in his article, i.e., that the Muslims follow

different ’sets of the Qur’an’ as if they are not all authoritative. One

wonders why did he choose to quote the material which does not even serve his

purpose! Further evidence against the view

in question may be drawn from the Qirâ’ât themselves. It is certainly germane

to the issue at hand to note that in many instances where the unmarked cUthmânic canon is capable of being read in

diverse ways, we find the Qurra (i.e., the Readers) agreeing on a single

reading. Such agreement can most reasonably be accounted for on the basis of a

firmly established oral tradition of recitation. Take for example the verbal

prefixes ta and ya (or tu or

yu), which in the unmarked text would be represented by the

same symbol. Taking the form turjacűna and yurjacűna as a case point we note that all the Qirâ’ât use

the first of these forms in 2:245; 10:56; 28:88; 36:22, 83; 39:44; 41:21 and

43:85; while all use the second in 6:36 and 19:40. There are also many words in the

Qur’an which could be given different form than the one given in the readings,

but in fact are not. For example, the word mukht in 17:106 is

so read by all the readers, although there is no reason why it could not be

read as mikth or makth. The verb khatifa-yakhtafu,

which appears in 2:20; 22:31 and 37:10 could be correctly read as khatafa-yakhtifu,

but all the Qirâ’ât keep the former form.[3] A few other examples can be shown by

refering to the books on Qirâ’ât. So, if the Qurra invented the

Qirâ’ât just because the earliest manuscripts were undotted, why then we see

that they had converged to one single reading many times? The Christian

missionary’s last resort will be to invoke two conspiracies on a massive scale

from The emphasis is that Muslims just

do not dump any readings as they all go back

to the famous Companions of the Prophet(P) such as Ubayy, Ibn Mascud, Zaid Ibn Thâbit and cUthmân(R). According to Samuel Green: > Fact 2. If

we now turn to an Islamic encyclopedia written by a practising Are we greatly surprised? A few

examples of the printed edition of masâhif

of the Qur’an in various Qirâ’ât are given below:

This is a well known and common mushâf printed in the

This is a mushâf

from

Yet another mushâf

in the riwaya of Warsh. This is printed in

The riwaya Qâlűn from Nâfic. This mushâf is published in

The Qur’an in the riwaya of Dűri from

Abî cAmrű. This mushâf is from

Only the canonical Arabic text, as collected and compiled

under the Caliph ‘Uthman with the consensus of the companions (Ijma as-Sahaabah)

may be recited, in one of the seven acceptable versions of the punctuation and

vocalization (al-Qira’at as-Sab). These,

though fixed only in the 4th century of the Hijrah, are taken to correspond to

the seven Ahruf (”letters”, “versions” or possibly “dialects”) of the Koran

which according to a hadith, the Prophet refered to as all having divine

authority. In practice, only two of the seven readings have become customary:

in So, we have the authority

directly from the Prophet(P) that the Qur’an can be recited in any of the

Qirâ’a. Indeed the presence of masâhif

of the Qur’an in different Qirâ’ât as well as the professional Muslim reciters

(and common folk too!) reciting the Qur’an in various Qirâ’ât indicates their

importance. There are people even in this day and age who recite in more than

one Qirâ’a and some of them upto ten. > Conclusion

2. According to this Islamic encyclopedia there are seven basic Samuel Green thinks he is pretty

clever. All of a sudden “Seven Basic Readings” now become “Seven Basic Texts”.

Further he confuses himself between ‘transmission’ and ‘text’ or probably he is

delibrately cheating as Katz did sometime ago. The ‘transmission’ was

conveniently changed into ‘text’ to show that Muslims have different Qur’ans. The Abuse of Brockett’s Material On Qirâ’ât The favourite article of the

Christian missionaries when dealing with the Qirâ’ât is that of Adrian Brockett

and is called “The Value of Hafs And Warsh Transmissions

For The Textual History Of The Qur’an“,

published in Approaches Of The History Of

Interpretation of The Qur’an. This book has been used by the

missionaries time and again to show different ‘texts’ of the Qur’an to the

Muslims. Adrian Brockett in no way supports the claim of the

Christian missionaries yet they still like to quote him for some strange

reason. Samuel Green quotes Adrian

Brockett’s article: > The simple

fact is that none of the differences, whether vocal or Is that all that is said in that

article or is it that Samuel Green’s hand suddenly turned heavy so that he

can’t lift the pages of that article? His aim is to show that there is a

‘corruption’ in the Qur’anic text. For that reason he has shown some images of the

difference in the graphic form. And now here comes Mr. Green’s audacity after

he admits his poor knowledge! The above

examples show that there are differences between the basic letters of these two

Qur’ans. These differences in the basic printed letters show that even the

basic text of Qur’an that Uthman standardised has not been perfectly preserved

for the different transmissions have small variation even in the basic text. If one goes back to page 34 of

the article, one can be read precisely the opposite: All this point to a remarkably unitary transmission in

both its graphic form and its oral form.[5] This, not surprisingly, was

conveniently omitted by Samuel Green. Conclusion 3.

There are real differences between the Qur’an according to the Hafs’

transmission and the Qur’an according to the Warsh’ transmission. There are

differences in the basic letters, diacritical dots, and vowels. These

differences are small, but they do have some effect on the meaning. Further, in the section The Extent To Which The Differences Affect The Sense,

Adrian Brockett states: The simple fact is that none of the differences, whether vocal or graphic,

between the transmission of Hafs and the transmission of Warsh has any great

effect on the meaning. Many are the differences which do not change the meaning

at all, and the rest are differences with an effect on the meaning in the

immediate context of the text itself, but without any significant wider

influence on Muslim thought.[6] And interestingly enough the

author went on to say: The limits of their variation clearly establish that they

are a single text.[7] That is something which Samuel

Green would not let us know unless, of course, we point out. We read further: Thus, if the Qur’an had been transmitted only orally for the first century,

sizeable variations between texts such as are seen in the hadith and

pre-Islamic poetry would be found, and if it had been transmitted only in

writing, sizeable variations such as in the different transmissions of the

original document of the constitution of Medina would be found. But neither is the case with the Qur’an.

There must have been a parallel written transmission limiting variation in the

oral transmission to the graphic form, side by side with a parallel oral

transmission preserving the written transmission from corruption.[8] This leads the author to state: The transmission of the Qur’an after the death of

Muhammad was essentially static, rather than organic. There was a single text,

and nothing significant, not even allegedly abrogated material, could be taken

out nor could anything be put in.[9] This leads anyone to the

conclusion that there is no tampering of the Qur’an by humans. In the end: There can be no denying that some of the formal

characteristics of the Qur’an point to the oral side and others to the written

side, but neither was as a whole, primary. There is therefore no need to make

different categories for vocal and graphic differences between transmissions.

Muslims have not. The letter is not a dead skeleton to be refleshed, but is a

manifestation of the spirit alive from beginning. The transmission of the

Qur’an has always been oral, just as it has been written.[10] The rest of the article which Mr.

Green surprisingly omitted says that the Qur’an is one and same text after the

death of Muhammad(P). So, this essentially refutes the whole

‘corruption’ argument of Mr. Green. No Books On Mutawâtir Readings Available? > MAIN

CONCLUSION. There are seven authorised readings of the Qur’an with Mr. Green’s admission is pretty

much honest that there are seven authorised readings of the Qur’an. Not many

missionaries are brave enough to admit it. We have to admit that his confession

has taken a rather torturous route. Further we read: > it is not

superior to other Holy Books. We request that Muslim leaders make As far as the fourteen Qirâ’ât

not being available, as suggested above, shows utter ignorance of the author.

If he had bother to check some of the Arabic literature on the issue of the

Qirâ’ât, we would not be hearing this nonsense. We have already shown above some

of the printed edition of the masâhif

of the Qur’an in different Qirâ’ât. Below are the examples of the

books which deals with ten mutawâtir

readings.

This book Al-Nashr fi-l-Qirâ’ât al-cAshr by Ibn al-Jazrî who died in 833 AH. This

is a standard book used by students of the science of Qirâ’ât. This is the

edition from Dâr al-Kutub cIlmiyyah, The below one a very recent book.

For the benefit of the English

speaking readers, we translate the Arabic in the above text.

The Ten Mutawâtir Readings from the ways of ash-Shatbiyyah

and ad-Durrah In the Margin of The Holy Qur’an an idea from cAlawi Ibn Muhammad Ibn Ahmad

Bilfaqih carried out by Shaykh Muhammad Karîm Râjih The Chief Reader in the Syrian

land Dâr al-Muhâjir for Publications &

Distribution

…unique and first work of this kind in the field of Science of the ten Mutawâtir readings from the

ways of ash-Shatbiyyah and ad-Durrah in the margin of the Holy Qur’an is now

achieved, edited, and printed.[11] The 10 readers/transmitters of

the Mutawâtir

readings are listed

here. What is more interesting is that there are reciters even to this day

who have memorised the Qur’an in all the 10 Mutawâtir

readings! In the end, I address Shaykh Kurayyim Râjih the Head of the

Readers in the Syrian lands with my gratitude for carrying out that work and

supervising its course and supplementing it with valuable guidelines that

hardly come from anyone except an expert like him. May God reward his kind student and reader Muhammad

Fahd Khârűf who masters the ten Mutawâtir readings from the ways of ash-Shatbiyyah

and ad-Durrah and at-Tibah for participating to this noble task

making it, with the divine help, a beneficial work

for the holders of God’s Almighty Book and his readers.[12] In any case, one more

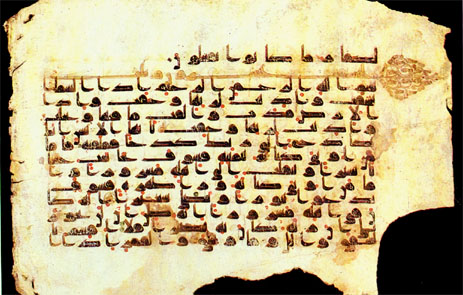

issue concerning the ‘lack of availability’ of the Qirâ’ât is down. We also present

the manuscript evidence that marks different Qirâ’ât and is dated probably 3rd

century AH. This is sufficient evidence to show that Qirâ’ât were given utmost

importance even in the past.

Probably 3rd

cent. A.H. no diacritical marks but advanced system of vocalization. Moreover,

this Mushaf marks the different canonical readings of the text

(Qirâ’ât). The process of restoring a masterpeice like this provides

the unique opportunity ot display the beauty and philological precision of one

Mushaf by showing more than just two pages.[13] It is clear from our discussion

about that the ‘variant’ readings of the Qur’an which are actually called

Qirâ’ât do not give the impression as ‘variant’ or something different than the

Qur’an. Muslims in the past as well as in the present have treated them with

utmost respect as they were all recited by the Prophet(P) and his Companions(R). They Qirâ’ât are just not considered as

something different from the Qur’an. One of the important conclusions

of the Christian missionary is also that: > the

evidence is considered. Since the Qur’an has variation within its text It will be good to study the

variant readings (they are truly variant!) in the New Testamant, their origins

and impact in the next section. It will be clear who exactly should be worried

about the variant readings and why should the Bible be considered as the last

candidate to be the ‘inerrant’ word of God. Variant Since this topic of variant

readings is brought forth and Mr. Green’s conclusion that since the Qur’an has

‘variation’ within its text and hence it is not superior to other Holy Books,

which presumably is the Bible. The

Interpreter’s Dictionary Of The Bible, Under “Text, NT“ informs

us that: THE PROBLEM. The NT

is now known, whole or in part, in nearly five thousand Greek MSS alone. Every

one of these handwritten copics differ from every other one. In addition to

these Greek MSS, the NT has been preserved in more than ten thousand MSS of the

early versions and in thousands of quotations of the Church Fathers. These MSS

of the versions and quotations of the Church Fathers differ from one another

just as widely as do the Greek MSS. Only a fraction of this great mass of

material has been fully collated and carefully studied. Until this task is

completed, the uncertainty regarding the text of the NT will remain. It has been estimated that these

MSS and quotations differ among themselves between 150,000 and 250,000 times.

The actual figure is, perhaps, much higher. A study of 150 Greek MSS of the

Gospel of Luke has revealed more than 30,000 different readings. It is true, of

course, that the addition of the readings from another 150 MSS of Luke would

not add another 30,000 readings to the list. But each MS studied does add

substantially to the list of variants. It is safe to say that there is

not one sentence in the NT in which the MS tradition is wholly uniform.[14] After reading this and applying

the conclusion of Mr. Green it would be quite clear that the Bible is not worth

even considering a scripture as it is clear that it is riddled with variant

readings and not a single sentence in the NT is uniform. Also

we do not know which one is the authorized reading. Some New Testament scholars

put the total number of readings or differences in the Bible at least 3,00,000

for 20th century. Hard to believe, is it not? Within this context, what NT textual materials have come down to us? As

early as 1707, John Mill claimed that the (relatively few) NT mss examined by

him contained about 30,000 variant readings (Vincent 1903: 6); 200 years later

B. B. Warfield (1907: 13) indicated that some 180,000 or 200,000 various

readings had been ‘counted’ in the then existing NT mss, and in more recent

times M. M. Parvis reported that examination of only 150 Greek mss of Luke

revealed about 30,000 readings there alone, and he suggested that the actual

quantity of variant readings among all NT manuscripts was likely to be much

higher than the 150,000 to 250,000 that had been estimated in modern times

(Parvis IDB 4: 594-95). Perhaps

300,000 differing readings is a fair figure for the 20th century (K. W. Clark

1962: 669). The textual critic must devise methods by which to sort through

these myriad readings and to analyze the many mss that contain them.[15] Further The Interpreter’s Dictionary Of The Bible

informs us: Many thousands of the variants which are found in the MSS

of the NT were put there deliberately. They are not merely the result of error

or of careless handling of the text. Many were created for theological or

dogmatic reasons (even though they may not affect the substance of Christian

dogma). It is because the books of the NT are religious books, sacred books,

canonical books, that they were changed to conform to what the copyist believed

to be the true reading. His interest was not in the “original reading but in

the “true reading.” This is precisely the attitude toward the NT which

prevailed from the earliest times to the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the

invention of printing. The thousands of Greek MSS, MSS of the versions, and

quotations of the Church Fathers provide the source for our knowledge of the

earliest or original text of the NT and of the history of the transmission of

that text before the invention of printing.[16] So, the tampering of the Bible

was done delibrately by the scribes themselves. It is pretty clear that Muslims

have a point when the tampering of the Bible is mentioned. Let us examine the reasons for

the corruption of the New Testament text. Bruce Metzger categorizes them as

Unintentional Errors and Intentional Changes.[17] 1. Unintentional errors

2. Intentional changes

So, if the Bible is really the

word of God then why did the scribes made intentional changes? Further do we

have the original copies of the Bible to verify what the original reading is

from the corrupted one? Since - like virtually all ancient literature - no

autographs are extant for the NT, its most likely original text must be

reconstructed from these imperfect, often widely divergent, later copies.[18] The interesting bit is not the

absence of original manuscripts but the presence of widely divergent and

imperfect readings. This is further exacerbated by the problem that we do not

have the original document to verify the original reading; therefore, we can

only make a guess of what the original reading could be. This means, we cannot

be sure whether Jesus(P) or Apostles said such a such thing in the Bible.

Hence it becomes a problem in evaluation of the Bible as a scripture. Indeed

the Acts of Apostles has earned the notoriety for the variant readings. In fact no book of the NT gives evidence of so much verbal variation as

does the Acts of Apostles. Besides the text represented in the oldest uncial

Greek MSS, begin with the Codex Vaticanus, often called the Neutral Text and

dating back to the second century AD, there is evidence either of a consistent

alternative text equally old, or of a series of early miscellaneous variants,

to which the name Western text is traditionally applied. The ancient

authorities of the Western Text of Acts include only one Greek (or rather

bilingual Greek and Latin) uncial MS, Codex Bezae of the fifth or sixth

century. But the variants often have striking content and strong early support

from Latin writers and Latin NT MSS. It now appears that while both the Neutral

and Western texts were in circulation, the former is the more likely of the two

to represent the original.[19] Apart from the notorious

variation we also have the problem of which text is the original text. Since we

do not know which one is original, the guess work in pressed into service. The

above problem is one such example of guess work. And how come guess work leads

to truth? Critical Editions & The Methodologies The argument would now be closed

by considering the issue of critical text which represents the variant readings

of the New Testament from the manuscripts as well as the quotes of the Church

Fathers. The widely used critical edition of New

Testament is by Nestle and Aland called Novum

Testamentum Graece Cum Apparatu Critico Curavit. This is a working

text or committee text which was agreed upon by a committee. This text was agreed by a committee. When they disagreed

on the best reading to print, they voted. Evidently, they agreed either by a

majority or unanimously that their text was the best available. But it does not

follow that they believed their text to be ‘original’. On the whole, the

textual critics have always been reluctant to claim so much. Other users of the

Greek New Testament accord them too much honour in treating the text as

definitive.[20] So, as far as the Novum Testamentum Graece (edited by Kurt

Aland and Barbara Aland) is concerned, one can say that the committee itself

does not make a claim that it restored the ‘original’ text of the Bible! So,

where is the original Bible then? In fact, the Kurt and

Barbara Aland, the editors of the recent edition of Nestle-Aland’s Novum Testamentum Graece Cum

Apparatu Critico Curavit compare the total number of variant free verses in

Nestle-Aland edition with the other critical editions such as that of

Tischendorf, Westcott-Hort, von Soden, Vogels, Merk, and Bover. It is

seen that nearly two-thirds of New Testament text in the seven editions of the

Greek New Testament reviewed by Aland and Aland is in agreement with no

differences other than in orthographic details.[21] Since Nestle-Aland’s critical

edition is very complicated to be used in the translation of the New Testament

in other languages, there was a growing need for new edition of Greek New

Testament which would serve this purpose. This need was materialised in the

form of The Greek New Testament, GNT2, (of course, based on Nestle-Aland’s critical

text) which has the following features:

An example of how the

GNT2 critical edition looks like is shown below. The above image

of the Gospel of Mark is taken from The Greek

New Testament edited by Kurt Aland,

Matthew Black, Carlo M Martini, Bruce M Metzger & Allen Wikgren. Note that

it provides lots of information on the textual variants and their relative

degree of certainity which are needed for the translation. This edition is similar

to the Nestle-Aland’s critical edition except

that it has more details on the textual variants and their relative degree of

certainity. By means of the letters A, B, C, and D, enclosed within “braces” { } at the

beginning of each set of textual variants the Committee has sought to indicate

the relative degree of certainity, arrived at the basis of internal

considerations as well as of external evidence, for the reading adopted as the

text. The letter A signifies that the text is virtually certain, while B

indicates that there is some degree of doubt. The letter C means that there is

a considerable degree of doubt whether the text or the apparatus contains the

superior reading, while D shows that there is a very high degree of doubt

concerning the reading selected for the text.[23] The relative degree

of certainity of the textual variants is again based on Committee discussions

which involved either a uanimous agreement or voting when they disagreed on a

particular reading. Also note that the textual variants are cited with their

relative degree of certainity. Certainly, if the New Testament’s original

text/literal text is available then why their relative degree of certainity? This clearly shows that the New Testament

that we have in our hands today is the work of human beings rather than the

word of God. So, by applying the standards of

the Christian missionary Samuel Green, we should reject the New Testament as a

’superior Holy Book’ because there is not a single sentence in it that is

uniform. Oh! we also forgot to mention that according to the great Church

tradition, we have the Bibles of the Protestant

Church, Roman

Catholic Church, Anglican

Church, Greek

Orthodox Church, Coptic

Church, Ethiopic

Church and Syriac

Church. They contain different number of books and God knows best how many

variants one is expected to see in them. So, our question now is which variants

and the books in the Bible are inspired by God? And what the evidence for it? And lastly we will let a

non-Muslim speak on the issue of the Islamic and the Christian scholarship

dealing with the ‘variants’: From an early date Muslim scholars recognized the danger of false testimony

and hence false doctrine, and developed an elaborate science for criticizing

tradition. “Traditional science”, as it was called, differed in many respects

from modern historical source criticism, and modern scholarship has always

disagreed with evaluations of traditional scientists about the authenticity and

accuracy of ancient narratives. But

their careful scrutiny of the chains of transmission and their meticulous

collection and preservation of variants in the transmitted narratives give to

medieval Arabic historiography a professionalism and sophistication without

precedent in antiquity and without parallel in the contemporary medieval West.

By comparison, the historiography of Latin Christendom seems poor and meagre,

and even the more advanced and complex historiography of Greek Christendom

still falls short of the historical literature of Islam in volume, variety and

analytical depth.[24] And Allah knows best! References [1] J M Cowan (Editor), Hans-Wehr Dictionary Of Modern Written Arabic, 1980 (Reprint), Librairie Du Liban, [2] W Muir, The Life Of Mohammad, 1912, Edinburgh, John Grant,

pp. xxii-xxiii. [3] Labib as-Said

(Translated By Bernard Weiss, M A Rauf & Morroe Berger), The Recited Koran, 1975, The [4] Cyril Glasse, The Concise Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1989, Stacey

International, [5] Andrew Rippin (Ed.), Approaches Of The History of Interpretation Of The Qur’an,

1988, Clarendon Press, [6] ibid., p. 37. [7] ibid., p. 43. [8] ibid., p. 44. [9] ibid. [10] ibid., p. 45. [11] cAlawi Ibn Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Bilfaqih,

Al-Qirâ’ât al-cAshr al-Mutawâtir, 1994, Dâr al-Muhâjir, See the back of

the cover page. [12] ibid. [13] Masâhif

San’â‘, 1985, Dâr

al-Athar al-Islâmiyyah, Mushâf no. 70, p. 36. [14] George Arthur Buttrick

(Ed.), The Interpreter’s Dictionary Of The Bible,

Volume 4, 1962 (1996 Print), Abingdon Press, [15] David Noel Freedman (Ed.), The Anchor Bible Dictionary On CD-ROM, 1997, [16] George Arthur Buttrick

(Ed.), The Interpreter’s Dictionary Of The

Bible, Volume 4, p. 595 (Under “Text,

NT“). [17] Bruce M Metzger, The Text Of The New Testament: Its Transmission,

Corruption & Restoration, 1992, [18] David Noel Freedman (Ed.), The Anchor Bible Dictionary On CD-ROM, (Under

“Textual Criticism, NT“). [19] George Arthur Buttrick

(Ed.), The Interpreter’s Dictionary Of The

Bible, Volume 1, p. 41 (Under “Acts of

the Apostles“). [20] D C Parker, The Living Text Of The Gospels, 1997, [21] Kurt Aland & Barbara

Aland, The Text Of The New Testament: An

Introduction To The Critical Editions & To The Theory & Practice Of

Modern Text Criticism, 1995, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company,

Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 29. [22] Kurt Aland, Matthew Black,

Carlo M Martini, Bruce M Metzger & Allen Wikgren (Editors), The Greek New Testament, 1968 (Second

Edition), United Bible Societies, p. v. [23] Ibid, pp. x-xi. [24] Bernard Lewis, Islam In History, 1993, Open Court

Publishing, pp.104-105. Taken from:The

Seven Readings Of The Qur’an By Samuel Green Refuted http://muslimresponse.wordpress.com/2008/09/10/quran-separated-in-variant-textual/ |

|||||||||