|

||||||||||

|

|

THE EDHI FOUNDATION,

KARACHI, PAKISTAN

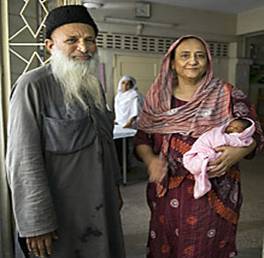

Top Left: In gritty

Karachi, husband-wife team saves unwanted babies

Abdul

Sattar Edhi and Bilquis Edhi are revered for their work over the last

half-century, pulling abandoned babies from the dumps and drains of this

Pakistani city. By Joel Elliott | Contributor to The

Christian Science Monitor from the July 14, 2008 edition Reporter Joel Elliott discusses

the Edhi Foundation in Karachi, Pakistan. KARACHI,

PAKISTAN

- Tiny, pink, and asleep in the arms of an

orphanage worker, Amna didn't know she had survived being abandoned two days

earlier in one of the world's grittiest cities. Nurses

had found her crying alone outside a local hospital – one of hundreds of babies

abandoned in Pakistan each year. But helped by the Edhi Foundation, a nonprofit

humanitarian organization based in Karachi, Amna soon would be adopted by a

local couple who had been unable to have children. The

heads of the foundation, the husband and wife team of Abdul Sattar Edhi and

Bilquis Edhi, have achieved a revered status for their work pulling abandoned

babies from the dumps and drains of Karachi and receiving them from mothers

with no questions asked. In

more than a half-century of work, they have rescued tens of thousands of babies

and – despite prejudice against such children – placed an estimated 16,700 in

adoptive homes. "It's

an amazing thing, because here in a society where there is no place for an

illegitimate child they are providing a place for them," says Meera Jamao,

a reporter for the newspaper Dawn. "People do hold [Mr. Edhi] in high

respect.... He is viewed as the Mother Teresa of Karachi." The

foundation has encountered resistance from religious leaders and other members

of the local community, the Edhis say, because it takes in abandoned babies

regardless of ethnicity or religion. The foundation makes an effort to match

babies with people who are of the religion of their parents, if it is known – a

highly sensitive issue among the country's religious leaders. "It's

very dangerous here," Mrs. Edhi says. "The mullahs right now only

threaten to kill us – if we gave a Muslim child to a non-Muslim family, they

would kill us for sure." But despite numerous death threats, they have

persisted. Today,

the Edhis and workers with the foundation say, they find fewer babies abandoned

in the dumps as mothers have become more aware of the service they provide. The

foundation's headquarters takes in about 300 abandoned babies each year, down

from a peak of about twice that number 30 years ago. As

the foundation has grown, it has occasionally been accused of corruption among

the lower-level staffers, but the Edhis continue to maintain a broad base of

support from the public. Mr. Edhi has gradually handed over the reins to his

son, Faisal Edhi, who has worked to bolster discipline and structure in the

institution, say observers. A partnership

based on charity The

couple's partnership began in 1964, when Bilquis, then 16, asked Abdul to let

her join the foundation, which he had been building for 14 years, to train and

work as a nurse. Though 20 years Bilquis's senior, Mr. Edhi soon proposed to

her – in the maternity ward – and they were married in 1966. By

1970, realizing that abandonment was far more widespread than they had thought,

the couple mounted a public education campaign and began placing cradles

throughout the city in hopes of encouraging mothers to leave their unwanted

babies anonymously. Today,

they maintain about 40 cradles in Karachi, and 350 others throughout the

country. Approximately 50,000 children at any given moment depend on the

foundation for their survival. Mrs. Edhi, a warm, motherly figure known

throughout the city as "Baji," or "big sister" in Urdu,

heads the foundation's baby rescue operation and free maternity ward in

Karachi. Mr. Edhi often rises as early as 3 a.m. to help feed some of the

orphans. With cropped white hair, a long beard, and a worn, homespun salwar

kameez, the traditional Pakistani dress, Mr. Edhi travels the country and

the world raising funds, efforts he characterizes as being "a beggar

before the public." The

Edhi Foundation also runs a number of other humanitarian-based operations, including

a country-wide ambulance service, maternity wards, hospitals, morgues, and

schools. The

problem of abandoned babies is partly a matter of economics, says Mr. Edhi.

"Our country is very, very poor," he explains, his spare frame

looking small behind a heavy wooden desk surrounded by posters of the

foundation's projects. "We have hundreds of thousands of hungry

people." Despite

its status as the country's center of commerce, Karachi's poverty rate is

around 50 percent, more than twice the rate of the country, according to a city

study. Impoverished couples often find themselves with no way to support their

growing families. With a female literacy rate of 43 percent and a deeply

entrenched dowry tradition, female babies are seen as a liability and thus

abandoned or even killed. The Edhis' records show that they find more than

twice as many abandoned girls as boys. While

tens of thousands of girls spend their days in the orphanages, many until they

are married, the Edhi Foundation keeps a waiting list of several thousand

families who want a baby boy. "I tell them, I don't make boys here,"

Mrs. Edhi says. "But with so many of the people, that's all they are

interested in." Screening

a potential adoptive couple Mrs.

Edhi fields dozens of inquiries daily about either adopting babies or else

leaving them in her care. Her phone rings constantly, and a string of visitors

files into her office from the dirty, crowded street that snakes through a

cluttered bazaar in downtown Karachi. On a

recent morning, a young couple entered her dimly lit office, silent except for

a few whispered exchanges. They carried documents indicating their annual

income, paper-clipped to a glossy photo of their wedding four years before.

They wanted a child because they were unable to conceive, Hamid Khan told Mrs.

Edhi. "They

were saying it was her problem," he said, referring to his wife, Rosina

Khan. "But it is not her problem, it is our problem. We love each other

and we don't want to split up." Mr.

Khan took out a cloth and began wiping away his tears as Mrs. Edhi interviewed

him and his wife. He explained that their parents had pressured them to

divorce. Theirs was a 'love marriage,' not an arranged one, and their parents

had taken their barrenness as a sign that the union was not meant to be.

Finally, the couple worked up the courage to ask Mrs. Edhi for a child.

Atypically, they wanted a girl. "My neighbor has a little girl, and I like

to play with her," says Mrs. Khan. "I'd like a daughter." Later,

Mrs. Edhi verifies the couple's information and places them on a waiting list.

She doesn't grant all requests. Families with children of their own are denied,

and Mrs. Edhi tries to weed out suspicious-sounding callers. In addition, the

foundation assumes most abandoned babies have been "born Muslim," and

will only place them in Muslim homes. Children

come to one of the Edhi Foundation's 20 homes around Pakistan as infants or

older and remain there until adulthood if they are not adopted or claimed by

their parents. Schools attached to the orphanages provide an education that

extends into the teen years. Some stay on and work for the foundation. Some

children who had lived their whole lives in the orphanages knew little or

nothing about their origins. "I have been here since I was a baby,"

says Mona, a teen who like others has taken Edhi as her last name. "I like

it very much. They are my parents, and this is my family." Information about the Edhi Foundation can be found at their

website: www.edhifoundation.com.

The Edhi Foundation does not accept donations from government agencies or

religious organizations, but will accept donations from individuals. http://www.csmonitor.com/2008/0714/p01s02-wosc.html# |

|||||||||