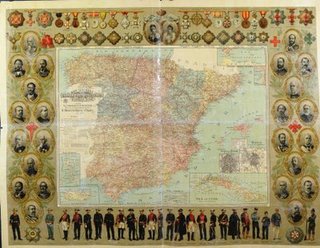

After a long and hard conquest,

the Iberian Peninsula became a region of the Roman Empire

known as Hispania. During the early Middle Ages  it

came under Germanic rule. Later it was conquered by Muslim invaders. Through a

very long and fitful process, the Christian kingdoms in the north gradually

rolled back Muslim rule, finally extinguishing its last remnant in Granada in

1492, the same year Columbus reached the Americas. A global empire began. Spain

became the strongest kingdom in Europe and the leading world power during the 16th century and

first half of the 17th century; but continued wars and other problems

eventually led to a diminished status. The French invasion of Spain in the early 19th century led to chaos; triggering

independence movements that tore apart most of the empire and left the country

politically unstable. In the 20th century it suffered a devastating civil war

and came under the rule of an authoritarian government, leading to years of

stagnation, but finishing in an impressive economic surge. Democracy was

restored in 1978 in the form of a parliamentry constitutional monarchy. In

1986, Spain joined the European Union; experiencing a cultural

renaissance and steady economic growth.

it

came under Germanic rule. Later it was conquered by Muslim invaders. Through a

very long and fitful process, the Christian kingdoms in the north gradually

rolled back Muslim rule, finally extinguishing its last remnant in Granada in

1492, the same year Columbus reached the Americas. A global empire began. Spain

became the strongest kingdom in Europe and the leading world power during the 16th century and

first half of the 17th century; but continued wars and other problems

eventually led to a diminished status. The French invasion of Spain in the early 19th century led to chaos; triggering

independence movements that tore apart most of the empire and left the country

politically unstable. In the 20th century it suffered a devastating civil war

and came under the rule of an authoritarian government, leading to years of

stagnation, but finishing in an impressive economic surge. Democracy was

restored in 1978 in the form of a parliamentry constitutional monarchy. In

1986, Spain joined the European Union; experiencing a cultural

renaissance and steady economic growth.

Prehistory and pre-Roman peoples

Archeological research at Atapuerca indicates the Iberian Peninsula was peopled 1.2 million years ago. Modern humans in the

form of Cro-Magnons began arriving in the Iberian Peninsula through the Pyrenees some

35,000 years ago. The best known artifacts of these prehistoric human

settlements are the famous paintings in the Altamira cave of Cantabria

in northern Spain, which were created about 15,000 BCE.

The two main historical peoples of the peninsula were the Iberians and the

Celts, the former  inhabiting

the Mediterranean side from the northeast to the southwest, the latter

inhabiting the Atlantic side, in the north and northwest part of the peninsula.

In the inner part of the peninsula, where both groups were in contact, a mixed,

distinctive culture—known as Celtiberian—was present. In addition, Basques

occupied the western area of the Pyrenees mountains. Other ethnic groups existed along the southern

coastal areas of present day Andalusia. Among these southern groups there grew the earliest urban

culture in the Iberian Peninsula, that of the semi-mythical southern city of Tartessos (perhaps pre-1100 BC) near the location of present-day

Cádiz. The flourishing trade in gold and silver between the people of Tartessos

and Phoenicians and Greeks is documented in the history of Strabo and in the

biblical book of king Solomon. Between about 500 BC and 300 BC, the seafaring

Phoenicians and Greeks founded trading colonies all along the Spanish

Mediterranean coast. Carthaginians briefly took control of much of the

Mediterranean coast in the course of the Punic Wars, until they were eventually

defeated and replaced by the Romans.

inhabiting

the Mediterranean side from the northeast to the southwest, the latter

inhabiting the Atlantic side, in the north and northwest part of the peninsula.

In the inner part of the peninsula, where both groups were in contact, a mixed,

distinctive culture—known as Celtiberian—was present. In addition, Basques

occupied the western area of the Pyrenees mountains. Other ethnic groups existed along the southern

coastal areas of present day Andalusia. Among these southern groups there grew the earliest urban

culture in the Iberian Peninsula, that of the semi-mythical southern city of Tartessos (perhaps pre-1100 BC) near the location of present-day

Cádiz. The flourishing trade in gold and silver between the people of Tartessos

and Phoenicians and Greeks is documented in the history of Strabo and in the

biblical book of king Solomon. Between about 500 BC and 300 BC, the seafaring

Phoenicians and Greeks founded trading colonies all along the Spanish

Mediterranean coast. Carthaginians briefly took control of much of the

Mediterranean coast in the course of the Punic Wars, until they were eventually

defeated and replaced by the Romans.

Roman Empire and Germanic invasions

During the Second Punic War, an expanding Roman Empire captured Carthaginian

trading colonies along the Mediterranean coast from roughly 210 BC to 205 BC,

leading to eventual Roman control of nearly the entire Iberian Peninsula; this

lasted over 500 years, bound together by law, language, and the Roman road.

The base Celt and Iberian population remained in various stages of

Romanisation, and local  leaders

were admitted into the Roman aristocratic class. Hispania served as a granary

for the Roman market, and its harbors exported gold, wool, olive oil, and wine.

Agricultural production increased with the introduction of irrigation projects,

some of which remain in use. Emperors Trajan, Theodosius I, and the philosopher

Seneca were born in Hispania. Christianity was introduced into Hispania in the

1st century CE and it became popular in the cities in the 2nd century CE. Most

of Spain's present languages and religion, and the basis of its

laws, originate from this period. Rome's loss of jurisdiction in Hispania began in 409, when the

Germanic Suevi and Vandals, together with the Sarmatian Alans crossed the Rhine

and ravaged Gaul until the Visigoths drove them into Iberia that same year. The Suevi established a kingdom in what is

today modern Galicia and northern Portugal. The Alans' allies, the Hasdingi Vandals, established a

kingdom in Gallaecia, too, occupying largely the same region but extending

further south to the Duero river. The Silingi Vandals occupied the region that still

bears a form of their name - Vandalusia, modern Andalusia, in Spain.

leaders

were admitted into the Roman aristocratic class. Hispania served as a granary

for the Roman market, and its harbors exported gold, wool, olive oil, and wine.

Agricultural production increased with the introduction of irrigation projects,

some of which remain in use. Emperors Trajan, Theodosius I, and the philosopher

Seneca were born in Hispania. Christianity was introduced into Hispania in the

1st century CE and it became popular in the cities in the 2nd century CE. Most

of Spain's present languages and religion, and the basis of its

laws, originate from this period. Rome's loss of jurisdiction in Hispania began in 409, when the

Germanic Suevi and Vandals, together with the Sarmatian Alans crossed the Rhine

and ravaged Gaul until the Visigoths drove them into Iberia that same year. The Suevi established a kingdom in what is

today modern Galicia and northern Portugal. The Alans' allies, the Hasdingi Vandals, established a

kingdom in Gallaecia, too, occupying largely the same region but extending

further south to the Duero river. The Silingi Vandals occupied the region that still

bears a form of their name - Vandalusia, modern Andalusia, in Spain.

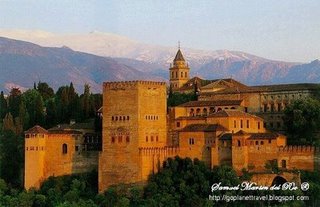

Muslim Iberia

Main article: Al-Andalus

In the 8th century, several areas of the Iberian Peninsula were conquered

(711-718) by mainly Muslims (see Moors) from North Africa.

These conquests were part of the expansion of the Umayyad Islamic Empire. Only

a number of areas in the north of the Iberian Peninsula managed to resist the

initial invasion, occupying areas roughly corresponding to modern Asturias, Navarre and northern Aragon.

Under Islam, Christians and Jews were recognised as "peoples of the

book", and were free to  practice

their religion, but faced a number of mandatory discriminations and penalties

as dhimmis. Conversion to Islam proceeded at a steadily increasing pace.

Following the mass conversions in the 10th and 11th centuries it is believed

that Muslims came to outnumber Christians in the remaining Muslim controlled

areas.

practice

their religion, but faced a number of mandatory discriminations and penalties

as dhimmis. Conversion to Islam proceeded at a steadily increasing pace.

Following the mass conversions in the 10th and 11th centuries it is believed

that Muslims came to outnumber Christians in the remaining Muslim controlled

areas.

The Muslim community in the Iberian

peninsula was itself diverse and

beset by social tensions. The Berber people of North Africa, who had provided

the bulk of the invading armies, clashed with the Arab leadership from the Middle East.

Over time, large Moorish populations became established, especially in the Guadalquivir River valley, the coastal plain of Valencia, and (towards the

end of this period) in the mountainous region of Granada.

Córdoba, the capital of the caliphate, was the largest, richest and most

sophisticated city of medieval western Europe. Mediterranean trade and cultural

exchange flourished. Muslims imported a rich intellectual tradition from the

Middle East and North Africa. Muslim and Jewish scholars played a great part in

reviving and expanding classical Greek learning in Western Europe.

The Romanized cultures of the Iberian

peninsula interacted with Muslim

and Jewish cultures in complex ways, thus giving the region a distinctive

culture. Outside the cities, where the vast majority lived, the land ownership

system from Roman times remained largely intact as Muslim leaders rarely

dispossessed landowners, and the introduction of new crops and techniques led

to a remarkable expansion of agriculture.

However, by the 11th century, Muslim holdings had fractured into rival Taifa

kingdoms, allowing the small Christian states the opportunity to greatly

enlarge their territories and consolidate their positions. The arrival of the

North African Muslim ruling sects of the Almoravids and the Almohads restored

unity upon Muslim holdings, with a stricter, less tolerant application of

Islam, but ultimately, after some successes in invading the north, proved

unable to resist the increasing military strength of the Christian states.

Fall of Muslim rule and unification

The Reconquista ("Reconquest") is the centuries-long period of

expansion of Spain's Christian kingdoms; Reconquista is viewed as beginning

with the battle of Covadonga in 722 and being concurrent with the period of

Muslim rule on the Iberian

peninsula. The Christian army's

victory over the Muslim forces led to the creation of the Christian

Kingdom of Astur ias

along the northern coastal mountains. Muslim armies had also moved north of the

Pyrenees, but they were defeated at the Battle of Poitiers in France. Subsequently, they retreated to more secure positions

south of the Pyrenees with a frontier marked by the Ebro and Duero rivers in Spain. As early as 739 Muslim forces were driven from Galicia, which was to host one of medieval Europe's

holiest sites, Santiago de Compostela. A little later Frankish forces

established Christian counties south of the Pyrenees; these areas were to grow

into kingdoms, in the north-east and the western part of the Pyrenees.

These territories included Navarre, Aragon and Catalonia.

ias

along the northern coastal mountains. Muslim armies had also moved north of the

Pyrenees, but they were defeated at the Battle of Poitiers in France. Subsequently, they retreated to more secure positions

south of the Pyrenees with a frontier marked by the Ebro and Duero rivers in Spain. As early as 739 Muslim forces were driven from Galicia, which was to host one of medieval Europe's

holiest sites, Santiago de Compostela. A little later Frankish forces

established Christian counties south of the Pyrenees; these areas were to grow

into kingdoms, in the north-east and the western part of the Pyrenees.

These territories included Navarre, Aragon and Catalonia.

The breakup of Al-Andalus into the competing Taifa kingdoms helped the

expanding Christian kingdoms. The capture of the central city of Toledo in 1085

largely completed the reconquest of the northern half of Spain. After a Muslim resurgence in the 12th century, the great

Moorish strongholds in the south fell to Christian Spain in the 13th

century—Córdoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248—leaving only the Muslim enclave of

Granada as a tributary state in the south. Marinid invasions from north Africa

in the 13th and 14th centuries failed to re-establish Muslim rule.  Also

in the 13th century, the kingdom of Aragon, formed by Aragon,

Catalonia and Valencia expanded its reach across the Mediterranean to Sicily. Around this time the universities of Palencia

(1212/1263) and Salamanca (1218/1254) were established; among the earliest in Europe. The

Black Death of 1348 and 1349 devastated Spain.

Also

in the 13th century, the kingdom of Aragon, formed by Aragon,

Catalonia and Valencia expanded its reach across the Mediterranean to Sicily. Around this time the universities of Palencia

(1212/1263) and Salamanca (1218/1254) were established; among the earliest in Europe. The

Black Death of 1348 and 1349 devastated Spain.

In 1469, the crowns of the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were united by the marriage of Isabella and Ferdinand. In

1478 began the final stage of the conquest of Canary Islands and in 1492, these

united kingdoms captured Granada, ending the last remnant of a 781-year

presence of Islamic rule in Iberia. The Treaty of Granada guaranteed religious

tolerance toward Muslims. The year 1492 also marked the arrival in the New

World of Christopher Columbus, during a voyage funded by Isabella. That same

year, Spain's Jews were ordered to convert to Catholicism or face

expulsion from Spanish territories during the Spanish Inquisition. Not long

after, Muslims were also expelled under the same conditions.

As Renaissance New Monarchs, Isabella and Ferdinand centralized royal power at

the expense of local nobility, and the word España - whose root is the ancient

name Hispania - began to be used commonly to designate the whole of the two

kingdoms. With their wide-ranging political, legal, religious and military

reforms, Spain emerged as the first world power.

Spanish Empire

Main article: Spanish Empire

The unification of the kingdoms of Aragon,

Castile, León, and Navarre laid the basis for modern Spain and the Spanish Empire. Spain

was Europe's leading power throughout the 16th century and most of

the 17th century, a position reinforced by trade and wealth from colonial

possessions. Spain reached its apogee during the reigns of the first two

Spanish Habsburgs -  Charles

I (1516–1556) and Philip II (1556–1598). This period also saw the Italian Wars,

the Dutch revolt, clashes with the Ottomans, the Anglo-Spanish war and war with

France.

Charles

I (1516–1556) and Philip II (1556–1598). This period also saw the Italian Wars,

the Dutch revolt, clashes with the Ottomans, the Anglo-Spanish war and war with

France.

The Spanish Empire expanded to include most parts of South and Central America,

Mexico, southern and western portions of today's United States, the Philippines, Guam and the Mariana Islands in Eastern Asia, parts of

northern Italy, southern Italy,

Sicily, cities in Northern Africa, as well as parts of France,

modern Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. It was the first empire about which it was said that the

sun never set. This was an age of discovery, with daring explorations by sea

and by land, the opening-up of new trade routes across oceans, conquests and

the beginnings of European colonialism. Along with the arrival of precious

metals, spices, luxuries, and new agricultural plants, Spanish and other

explorers brought back knowledge from the New World,

playing a leading part in transforming Europeans understanding of the globe.

The cultural efflorescence witnessed is now referred to as the Spanish Golden

Age.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Spain was confronted by unrelenting challenges from all sides.

Barbary pirates under the aegis of the rapidly growing Ottoman empire,

disrupted life in many coastal areas through their slave raids and renewed the

threat of an Islamic invasion. This at a time when Spain

was often at war with France in Italy and elsewhere. Later the Protestant Reformation schism

from the Catholic Church dragged the kingdom ever more deeply into the mire of

religiously charged wars. The result was a country forced into ever expanding

military efforts across Europe and in the Mediterranean.

The rise of humanism, the Protestant Reformation and new geographical

discoveries raised issues addressed by an intellectual movement known as the School

of Salamanca.

By the middle decades of a war and plague ridden 17th century Europe, the  effects

of the strain began to show. The Spanish Habsburgs had enmeshed the country in

the continent wide religious-political conflicts. These conflicts drained it of

resources and undermined the European economy generally. Spain managed to hold

on to most of the scattered Habsburg empire, and help the imperial forces of

the Holy Roman Empire reverse a large part of the advances made by Protestant

forces, but it was finally forced to recognise the separation of Portugal (with

whom it had been united in a personal union of the crowns from 1580 to 1640)

and the Netherlands, and eventually suffered some serious military reverses to

France in the latter stages of the immensely destructive, Europe-wide Thirty

Years War.

effects

of the strain began to show. The Spanish Habsburgs had enmeshed the country in

the continent wide religious-political conflicts. These conflicts drained it of

resources and undermined the European economy generally. Spain managed to hold

on to most of the scattered Habsburg empire, and help the imperial forces of

the Holy Roman Empire reverse a large part of the advances made by Protestant

forces, but it was finally forced to recognise the separation of Portugal (with

whom it had been united in a personal union of the crowns from 1580 to 1640)

and the Netherlands, and eventually suffered some serious military reverses to

France in the latter stages of the immensely destructive, Europe-wide Thirty

Years War.

In the latter half of the 17th century, Spain

went into a gradual relative decline, during which it surrendered a number of

small territories to France. However Spain maintained and enlarged its vast overseas empire, which

remained intact until the beginning of the 19th century.

The decline culminated in a controversy over succession to the throne which

consumed the first years of the 18th century. The War of Spanish Succession, a

wide ranging international conflict combined with a civil war, cost Spain its European possessions and its position as one of the

leading powers on the Continent.

During this war, a new dynasty—the French Bourbons—was installed. Long united

only by the Crown, a true Spanish state was established when the first Bourbon

king Philip V of Spain united Castile and Aragon into a single state, abolishing many of the regional

privileges (fueros).

The 18th century saw a gradual recovery and an increase in prosperity through

much of the empire. The new Bourbon monarchy drew on the French system of

modernising the administration and the economy. Enlightenment ideas began to

gain ground among some of the kingdom's elite and monarchy. Towards the end of

the century trade finally began growing strongly. Military assistance for the

rebellious British colonies in the American War of Independence improved Spain's international standing.

Napoleonic rule and its consequences

In 1793, Spain went to war against the new French Republic, which had overthrown and executed its Bourbon king, Louis

XVI. The war polarised the country in an apparen t

reaction against the gallicised elites. Defeated in the field, Spain

made peace with France in 1795 and effectively became a client state of that

country; the following year, it declared war against Britain and Portugal. A disastrous economic situation, along with other

factors, led to the abdication of the Spanish king in favour of Napoleon's

brother, Joseph Bonaparte.

t

reaction against the gallicised elites. Defeated in the field, Spain

made peace with France in 1795 and effectively became a client state of that

country; the following year, it declared war against Britain and Portugal. A disastrous economic situation, along with other

factors, led to the abdication of the Spanish king in favour of Napoleon's

brother, Joseph Bonaparte.

This foreign puppet monarch was widely regarded with scorn. On 2 May 1808, the

people of Madrid began a nationalist uprising against the French army, one

of many across the country, marking the beginning of what is known to the

Spanish as the War of Independence, and to the English as the Peninsular War.

Napoleon was forced to intervene  personally,

defeating several badly-coordinated Spanish armies and forcing a British Army

to retreat to Corunna. However, further military action by Spanish guerrillas

and Wellington's Anglo-Portuguese army, combined with Napoleon's

disastrous invasion of Russia, led to the ousting of the French from Spain in 1814, and the return of King Ferdinand VII.

personally,

defeating several badly-coordinated Spanish armies and forcing a British Army

to retreat to Corunna. However, further military action by Spanish guerrillas

and Wellington's Anglo-Portuguese army, combined with Napoleon's

disastrous invasion of Russia, led to the ousting of the French from Spain in 1814, and the return of King Ferdinand VII.

The French invasion proved disastrous for Spain's economy, and left a deeply divided country that was

prone to political instability for more than a century. The power struggles of

the early 19th century led to the loss of all of Spain's

colonies in Latin America, with the exception of Cuba

and Puerto Rico.

Spanish-American War

Main article: Spanish–American War

Amid the instability and economic crisis that afflicted Spain

in the 19th century there arose nationalist movements in the Philippines and Cuba. Wars of independence ensued in those colonies and

eventually the United

States

became involved. Despite the commitment and ability shown by some military

units, they were so mismanaged by the highest levels of command that the

Spanish-American war of 1898 was soon over. "El Desastre" (The

Disaster), as the war became known in Spain, helped give impetus to the

Generation of 98 who were already conducting much critical analysis concerning

the country. It also weakened the stability that had been established during

Alfonso XII's reign.

20th century

The 20th century brought little peace; Spain

played a minor part in the scramble for Africa, with the colonisation of

Western Sahara, Spanish Morocco and Equatorial Guinea. The heavy losses suffered during the Rif war in Morocco helped to undermine the monarchy. A period of

authoritarian rule under General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923-1931) ended wi th

the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic. The Republic offered political autonomy to the Basque

Country, Catalonia and Galicia and gave voting rights to women.

th

the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic. The Republic offered political autonomy to the Basque

Country, Catalonia and Galicia and gave voting rights to women.

The bitterly fought Spanish Civil War (1936-39) ensued. Three years later the

Nationalist forces, led by General Francisco Franco, emerged victorious with

the support of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The Republican side was

supported by the Soviet Union and Mexico and international brigades , most famously the american

'Abraham Lincon Brigade', but it was not supported officially by the Western

powers due to the British-led policy of Non-Intervention. The Spanish Civil War

has been called the first battle of the Second World War; under Franco, Spain was neutral in the Second World War though sympathetic to

the Axis.

The only legal party under Franco's regime was the Falange española

tradicionalista y de las JONS, formed in 1937; the party emphasised

anti-Communism, Catholicism and nationalism. Nonetheless, since Franco's

anti-democratic ideology was opposed to the idea of political parties, the new

party was renamed officially a National Movement (Movimiento Nacional) in 1949.

After World War II, Spain was politically and economically isolated, and was kept

out of the United Nations until 1955, when due to the Cold War it became

strategically important for the U.S.

to create a military presence on the Iberian peninsula, next to the

Mediterranean Sea and the Strait of Gibraltar, in order to protect southern Europe. In

the 1960s, Spain registered an unprecedented economic growth in what was called

the Spanish miracle, which rapidly resumed the long interrupted transition

towards a modern industrial economy with a thriving tourism sector and a high

degree of human development.

Upon

the death of General Franco in November 1975, Prince Juan Carlos assumed the

position of king and head of state. With the approval of the new Spanish

Constitution of 1978 and the arrival of democracy, the State devolved autonomy

to the regions and created an internal organization based on autonomous

communities. In the Basque Country, moderate Basque nationalism coexisted with

a radical nationalism supportive of the separatist group ETA.

Upon

the death of General Franco in November 1975, Prince Juan Carlos assumed the

position of king and head of state. With the approval of the new Spanish

Constitution of 1978 and the arrival of democracy, the State devolved autonomy

to the regions and created an internal organization based on autonomous

communities. In the Basque Country, moderate Basque nationalism coexisted with

a radical nationalism supportive of the separatist group ETA.

On 23 February 1981, rebel elements among the security forces seized the Cortes

and tried to impose a military-backed government. However, the great majority

of the military forces remained loyal to King Juan Carlos, who used his

personal authority and addressed the usurpers via national TV as commander in

chief to put down the bloodless coup attempt.

On 30 May 1982, NATO gained a new member when, following a referendum, the

newly democratic Spain joined the alliance. Also in 1982, the Spanish Socialist

Workers Party (PSOE) came to power, representing the return of a left-wing

government after 43 years. In 1986, Spain joined the European Community - what has now become the

European Union. The PSOE was replaced in government by the Partido Popular (PP)

after the latter won the 1996 General Elections; at that point the PSOE had

served almost 14 consecutive years in office.

The Government of Spain has been involved in a long-running campaign against

the separatist and terrorist organization ETA ("Basque Homeland and

Freedom"), founded in 1959 in opposition to Franco and dedicated to

promoting Basque independence through violent means. They consider themselves a

guerrilla organization while they are listed as a terrorist organization by

both the European Union and the United States on their respective watchlists. The current

nationalist-led Basque Autonomous government does not endorse ETA's nationalist

violence, which has caused over 800 deaths in the past 40 years.

21st century

On 1 January 2002, Spain terminated its peseta currency and replaced it with the

euro, which it shares with 14 other countries in the Eurozone. Spain has also seen strong economic growth, well above the EU

average, but concerns are growing that the extraordinary property boom and high

foreign

trade deficits of recent years may bring this to an end.

foreign

trade deficits of recent years may bring this to an end.

A series of bombs exploded in commuter trains in Madrid, Spain on 11 March 2004. After a five month trial in 2007 it was

concluded the bombings were perpetrated by a local Islamist militant group

inspired by al-Qaeda. The bombings killed 191 people and wounded more than

1800, and the intention of the perpetrators may have been to influence the

outcome of the Spanish general election, held three days later. Though initial

suspicions focused on the Basque group ETA, evidence soon emerged indicating

possible Islamist involvement. Because of the proximity of the election, the

issue of responsibility quickly became a political controversy, with the main

competing parties PP and PSOE exchanging accusations over the handling of the

aftermath. At the 14 March elections, PSOE, led by José Luis Rodríguez

Zapatero, obtained a relative majority, enough to form a new cabinet with

Rodríguez Zapatero as the new Presidente del Gobierno or prime minister of Spain, thus succeeding the former PP administration.

Posted

by Travel at 19:22

http://goplanettravel.blogspot.com/2008/11/spanish-history.html