Islamic

Jihad vs. the Western Way

of War

Islamic

Jihad vs. the Western Way

of War

By Fjordman

I had a conversation recently with a good

friend of mine regarding the situation in Western Europe,

with rapidly rising ethnic and religious tensions caused by mass immigration.

Historically, the usual situation is that Muslims keep the lands they have

taken possession of. There are a few exceptions, for instance with the Reconquista

in the Iberian Peninsula, but this took

centuries. If this pattern still holds up, the situation does admittedly look

bleak.

The problem is that the circumstances this time around are very special. We are

dealing with the unprecedented situation where a militarily inferior group is

allowed by the authorities in technologically stronger countries to settle in

their lands and harass the local population. Muslims havent actually defeated

us in warfare. Do the old rules then apply? Nobody knows for certain. It is

difficult to predict the future, apart from the fact that there will be a lot

of turbulence here in the coming years and decades.

In my book Defeating

Eurabia I quoted the American scholar Daniel Pipes, who believes that

the decisive events in Europe have yet to take place, perhaps within the next

decade or so. As Pipes puts

it, the situation is historically unprecedented: No large territory has

ever shifted from one civilization to another by virtue of a collapsed

population, faith, and identity; nor has a people risen on so grand a scale to

reclaim its patrimony. The novelty and magnitude of Europes

predicament make it difficult to understand, tempting to overlook, and nearly

impossible to predict. Europe marches us all

into terra incognita.

I write about European history in order to gain inspiration from our past so

that we can face the future with self-confidence. While reading about our

artistic and scientific contributions to world culture is inspiring, we should

not leave out our military traditions. They, too, constitute a part of our

heritage, and we may soon need to revive some of those traditions. In The

Cambridge History of Warfare, Geoffrey Parker states that the Western way of war boasts

great antiquity and great continuity, with emphasis on technology and

organization:

First, the armed forces of the West have always placed heavy reliance on

superior technology, usually to compensate for inferior numbers. That is not to

say that the West enjoyed universal technological superiority until the advent of musketry volleys and

field artillery in the early seventeenth century, the recurved bow used by

horse archers all over Asia proved far more effective than any western

weaponry but, with few exceptions, the

horse archers of Asia did not directly threaten the West and, when they did,

the threat was not sustained. Nor did all the advanced technology originate in

the West: many vital innovations, including the stirrup and gunpowder, came

from eastern adversaries. Normally, military technology is the first to be

borrowed by every society, because the penalty for failing to do so can be

immediate and fatal; but the West seems to have been preternaturally receptive

to new technology, whether from its own inventors or from outside.

Technological innovation, and the equally vital ability to respond to it, soon

became an established feature of western warfare.

An effective pre-modern use of chemical innovations in warfare was the

flammable substance known as Greek fire, which was employed by the Christians

of the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire in the seventh century to set ablaze the

attacking Muslim fleet. The Byzantines lost important provinces to Muslims, but

managed to salvage Constantinople and thus

ensure the survival of a diminished version of their Empire for many centuries

to come.

According to historian Raymond Ibrahim,

the author of the book The Al Qaeda Reader , âThough many historians have

rightly hailed the somewhat contemporary Battle of Tours of 732, where Charles

the Hammer repulsed the invading Muslim armies, as one of the most decisive

victories for Western civilization, in fact, the Byzantine victory over the

Muslims is more important: it had the full backing of the caliphate, and

consisted of far greater manpower. Had the Muslims won, and since Byzantium was the bulwark of Europes eastern flank, there

would have been nothing in their way from turning the whole of Europe into the north-western appendage of Dar al-Islam.

One of the greatest revolutions in the history of warfare began with the

Chinese invention of gunpowder. The Mongol conquests spread the knowledge of

gunpowder across Eurasia in the thirteenth

century, although it is possible that some information regarding the invention

had followed normal trade routes before this. The Mongols never reached Western

Europe, yet they did a brief, but damaging invasion of Eastern Europe and had a

lasting impacting on Ukrainian and Russian history after the destruction of the

great city of Kiev.

According to Arnold Pacey in Technology in World Civilization: A

Thousand-Year History, Four years after the invasion of 1241, the pope sent

an ambassador to the Great Khans capital in Mongolia. Other travellers followed

later, of whom the most interesting was William of Rubruck (or Ruysbroek). He

returned in 1257, and in the following year there are reports of experiments

with gunpowder and rockets at Cologne.

Then a friend of William of Rubruck, Roger Bacon, gave the first account of

gunpowder and its use in fireworks to be written in Europe.

A form of gunpowder had been known in China since before AD 900, and as

mentioned earlier, in 1040 some recipes for gunpowder mixtures appeared in a

printed book. One mixture was for making incendiary weapons and another gave a

mild explosive. Rockets were invented in China before 1150, and a gunpowder

formula which produced violent explosions was known a century later. Much of

this knowledge had reached the Islamic countries by then, and the saltpetre

used in making gunpowder there was sometimes referred to, significantly, as

Chinese snow. The Mongols did not have gunpowder weapons in Hungary in

1241, but acquired them from the Chinese soon after. - - -

- - - - - -

Gunpowder (black powder) consists of charcoal, sulphur and

potassium nitrate, or saltpeter, and was impossible to create until you could

manufacture saltpeter with some degree of purity. This was a specialty of Chinese

alchemists quite early. Gunpowder was definitely known in China by the

eleventh century and probably some generations prior to this, possibly before

AD 900. The English theologian and scholar Roger Bacon and the German friar and

scholar Albertus Magnus, also known as Albert the Great or Albert of Cologne,

both mentioned a recipe for gunpowder in the late thirteenth century. Black

powder remained the principle explosive until the Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel

patented dynamite in 1867.

While the first crude handguns and weapons employing

gunpowder were invented by the Chinese themselves, it appears that Europeans

were the first to invent large cannons, in the decades before and after the

year 1300. By 1500 the manufacture of guns had become a universal technology

among all major Eurasian civilizations. Arnold Pacey writes:

Bronze barrels for cannon were being produced in such

quantity and in so many countries by about 1500 that one historian has called

this a second bronze age. Not only was there large-scale production in Europe,

the Ottoman Empire, India

and China, but before 1650

guns had been manufactured in Korea,

Japan, Siam and Iran,

and occasionally in many other places, notably Benin, the famous West African

bronze-casting centre. Since bronze was an alloy of copper with small amounts

of tin, the mining of these metals expanded greatly. Copper was exported by Japan in the east and Sweden

in the west, and tin mining developed fast in Malaya.

All this can be traced back to the small hand-guns made in China before 1288, which stimulated the

development of large cannon, first in Europe (before 1320), then in the Islamic

world (1330s) and in China

itself (1356). Beyond this, the acquisition of guns by Korea during the 1370s is of interest as a

well-documented transfer of technology from China. No other countries are known

to have obtained gun-making technology from China, where methods and designs

were both conservative and protected by secrecy, but many nations obtained guns

through contact with the Portuguese.

Interestingly enough, firearms reached Japan in the

mid-sixteenth century with Portuguese adventurers who came from the other side

of the world, not from neighboring China. While the Chinese were the first to

use gunpowder in warfare, the most dynamic development of such weapons took

place in Europe. A Jesuit mission in Beijing provided

gun-making expertise to the natives during the downfall of the Ming Dynasty in

the 1640s.

Interestingly enough, firearms reached Japan in the

mid-sixteenth century with Portuguese adventurers who came from the other side

of the world, not from neighboring China. While the Chinese were the first to

use gunpowder in warfare, the most dynamic development of such weapons took

place in Europe. A Jesuit mission in Beijing provided

gun-making expertise to the natives during the downfall of the Ming Dynasty in

the 1640s.

According to Harry G. Gelber in The Dragon and the Foreign Devils: China and the

World, 1100 B.C. to the Present, âgunpowder had long since been a Chinese

invention, but the Ming showed comparatively little interest in its military

applications. After all, using crossbows from behind walls was quite effective

against nomad cavalry. The Mongols had already used cannon in their sieges and

even the Ming had some early muskets and bombs, but it was not until the

Japanese invaders of Korea

had used cannon successfully in the 1590s that the Chinese condescended to

learn much about them. In 1621, when the Portuguese offered four cannon to the

emperor, they found they had to send cannoneers with them. The following year

the court asked Jesuits from Macao to cast

cannon for China

and twenty years later another of them, Adam Schall himself, was asked to cast

more and teach the Chinese how to make them. In fact, some of the old Jesuit

cannon were still being used in the nineteenth century.â

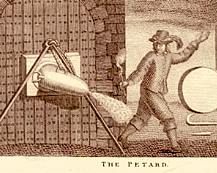

At the outset of the Hundred Yearsâ War (1337-1453), the

primary means of combat remained the longbow, the crossbow, the pike and the armored

knight mounted on an armored charger. At the end, gunpowder artillery won out.

Joan of Arc (1412-31), an illiterate peasant girl, could be militarily useful

during this transitional period with new technology. She became a national

symbol for France,

which emerged as a strong entity in fifteenth century.

The âgunpowder revolutionâ facilitated the rise of large,

expensive armies and centralized states. The new weaponry rendered medieval

castles and city walls obsolete. Because of the cost of keeping abreast of

changing technology and of maintaining the resources to deploy it effectively,

relatively few states proved able to remain in the race. Some, like Denmark, proved too small, while others, like Poland after

1667, too fragmented. James E. McClellan and Harold Dorn write in Science and Technology in World History , second

edition:

The âgunpowder revolutionâ facilitated the rise of large,

expensive armies and centralized states. The new weaponry rendered medieval

castles and city walls obsolete. Because of the cost of keeping abreast of

changing technology and of maintaining the resources to deploy it effectively,

relatively few states proved able to remain in the race. Some, like Denmark, proved too small, while others, like Poland after

1667, too fragmented. James E. McClellan and Harold Dorn write in Science and Technology in World History , second

edition:

âThe musket was introduced in the 1550s, and in their

reforms Maurice and William Louis of Nassau instituted volley fire by extended

rows of musketeers using standardized muskets and coordinated routines of

loading and firing. Those reforms and standardized field artillery made for

potent new armies from 1600. In the face of muskets and artillery, longbows,

crossbows, broadswords, cavalry, and pikemen exercised diminished roles or

vanished entirely from the scene of the battle. Infantry, now bristling with

handguns, once again became a dominant arm on the field of battle. As a result,

over the next two centuries the size of standing armies of several European

states jumped dramatically from the range of 10,000 to 100,000 soldiers. During

the last 70 years of the seventeenth century alone the French army grew from

150,000 to perhaps 400,000 under the Sun King, Louis XIV.â

In addition to technology, Western military practice has

generally exalted discipline in the form of drill and long-term service. It is

wrong to assume that Europeans during their first contact with Asians in the

early modern era were always technologically superior. Indians had made fine

guns from brass since the sixteenth century. Europeans at the time did not have

good methods for smelting zinc, which was done extensively in India and China. Brass was made in large

quantities in Britain and Germany by the

mid-eighteenth century. It is not clear whether this was based on imported

Asian techniques, but this remains plausible.

According to Pacey, âBritainâs âconquestâ of India cannot be

attributed to superior armaments. Indian armies were also well equipped. More

significant was the prior breakdown of Mughal government and the collaboration

of many Indians. Some victories were also the result of good discipline and

bold strategy, especially when Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington,

was in command. Wellesleyâs contribution also illustrates the distinctive

western approach to the organizational aspect of technology. Indian armies

might have good armament, but because their guns were made in a great variety

of different sizes, precise weapons drill was impossible and the supply of shot

to the battlefield was unnecessarily complicated. By contrast, Wellesleyâs

forces standardized on just three sizes of field gun, and the commander himself

paid close attention to the design of gun carriages and to the bullocks which

hauled them, so that his artillery could move as fast as his infantry, and

without delays due to wheel breakages. Significantly, the one major criticism

regularly made of Indian artillery concerned the poor design of gun carriages.

Many, particularly before 1760, were little better than four-wheeled trolleys.

But the guns themselves were often of excellent design and workmanship.â

Ironically, Westerners have often performed at our best when we

have been the underdogs. As Geoffrey Parker states, âOnce again, the crucial

advantage lay in the ability to compensate for numerical inferiority, for

whether defending Europe from invasion (as at Plataea in 479 BC, at the

Lechfeld in AD 955 and at Vienna in AD 1683), or in subduing the Aztec, Inca

and Mughal empires, the western forces have always been outnumbered by at least

two to one and often by far more. Without superb discipline as well as advanced

technology, these odds would have proved overwhelming. Even Alexander the Great

and his 60,000 Greek and Macedonian troops could scarcely have destroyed the

forces of the Persian empire in the fourth century BC without superior

discipline, since his adversaries probably numbered more Greek soldiers

(fighting with much the same equipment) in their own armies!â

Ironically, Westerners have often performed at our best when we

have been the underdogs. As Geoffrey Parker states, âOnce again, the crucial

advantage lay in the ability to compensate for numerical inferiority, for

whether defending Europe from invasion (as at Plataea in 479 BC, at the

Lechfeld in AD 955 and at Vienna in AD 1683), or in subduing the Aztec, Inca

and Mughal empires, the western forces have always been outnumbered by at least

two to one and often by far more. Without superb discipline as well as advanced

technology, these odds would have proved overwhelming. Even Alexander the Great

and his 60,000 Greek and Macedonian troops could scarcely have destroyed the

forces of the Persian empire in the fourth century BC without superior

discipline, since his adversaries probably numbered more Greek soldiers

(fighting with much the same equipment) in their own armies!â

Moreover, âThis military edge meant that the West seldom

suffered successful invasion itself. Armies from Asia and Africa rarely marched

into Europe and many of the exceptions â

Xerxes, Hannibal, Attila, the Arabs and the Turks â achieved only limited

success. None encompassed the total destruction of their foe. Conversely,

western forces, although numerically inferior, not only defeated the Persian

and Carthaginian invaders but managed to extirpate the states that sent them.

Even the forces of Islam never succeeded in partitioning Europe

into âspheres of influenceâ in the western manner. On the other hand,

however, time and again a favourable balance of military power critically

advanced western expansion.â

We must look at the theory of European warfare, too. The

overall aim of Western strategy usually remained the total defeat and

destruction of the enemy, and this contrasted starkly with the military

practice of many other societies. The German (Prussian) general and military

thinker Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831) gained practical experience during the

Napoleonic wars. His great work Vom Kriege (On War) was published

posthumously by his wife in 1832 and is still studied carefully at military

academies around the world. However, Clausewitzâs work is deeply tied to the

modern state structure. It is not clear whether all his theories will be

applicable in the case of civil wars and ethnic warfare within failing nation

states, which we may unfortunately face in the twenty-first century in a number

of Western countries due to ethnic tensions caused by runaway mass immigration

from alien cultures.

Arguably the greatest treatise on war ever written in any nation

or age is The Art of War, traditionally ascribed to the Chinese military

strategist Sun Tzu or Sunzi.

Scholars who believe that he was an historical person (a view which is disputed

by some non-traditionalists) often place him early in the Warring States Period

(476-221 BC), perhaps in the fifth century BC. Whether he is an historical

person or not, The Art of War is undoubtedly very old, yet has remained

surprisingly fresh to this day with its advice on information gathering

regarding the enemyâs troops and dispositions and its emphasis on

flexibility, deceit and psychological warfare. According to Sun Tzu, âSeizing

the enemy without fighting is the most skillful.â

Arguably the greatest treatise on war ever written in any nation

or age is The Art of War, traditionally ascribed to the Chinese military

strategist Sun Tzu or Sunzi.

Scholars who believe that he was an historical person (a view which is disputed

by some non-traditionalists) often place him early in the Warring States Period

(476-221 BC), perhaps in the fifth century BC. Whether he is an historical

person or not, The Art of War is undoubtedly very old, yet has remained

surprisingly fresh to this day with its advice on information gathering

regarding the enemyâs troops and dispositions and its emphasis on

flexibility, deceit and psychological warfare. According to Sun Tzu, âSeizing

the enemy without fighting is the most skillful.â

Other military cultures such as those of East

Asia also placed a high premium on technology and discipline.

However, the West differed in its unique ability to change and conserve its

military practices as need arose and in its power to finance those changes.

Underlying the strength of their militaries has been the strength of Western

economies. Geoffrey Parker:

âHarlech castle, one of Edward Iâs magnificent

fortifications in Wales,

cost almost an entire yearâs revenue to build, but in 1294 its garrison of

only thirty-seven soldiers successfully defended it against attack. The

kingâs strategic vision anticipated that of the âManhattan Projectâ,

which spent millions of dollars on the production of nuclear devices which,

delivered on two August mornings in 1945 by just two airplanes, precipitated

the unconditional surrender of Imperial Japan and the millions of her troops still

in arms all over southeast Asia. After the introduction of gunpowder weapons

and defences, the costâŚof military hardware rose to such a degree that only a

centralized state could afford to buyâŚ.Naturally, the less developed the

economy, the less easily the cost of military preparedness could be absorbed

â even within the West. Thus in 1904, France spent 36 per cent of her budget

on the army whereas Germany spent only 20 per cent; however, in real terms this

meant that France spent only thirty-eight million francs as against ninety-nine

million by Germany. Thus France devoted twice as much of her budget in order to

spend only half as much as her major rival.â

âHarlech castle, one of Edward Iâs magnificent

fortifications in Wales,

cost almost an entire yearâs revenue to build, but in 1294 its garrison of

only thirty-seven soldiers successfully defended it against attack. The

kingâs strategic vision anticipated that of the âManhattan Projectâ,

which spent millions of dollars on the production of nuclear devices which,

delivered on two August mornings in 1945 by just two airplanes, precipitated

the unconditional surrender of Imperial Japan and the millions of her troops still

in arms all over southeast Asia. After the introduction of gunpowder weapons

and defences, the costâŚof military hardware rose to such a degree that only a

centralized state could afford to buyâŚ.Naturally, the less developed the

economy, the less easily the cost of military preparedness could be absorbed

â even within the West. Thus in 1904, France spent 36 per cent of her budget

on the army whereas Germany spent only 20 per cent; however, in real terms this

meant that France spent only thirty-eight million francs as against ninety-nine

million by Germany. Thus France devoted twice as much of her budget in order to

spend only half as much as her major rival.â

Another key feature of the Western tradition is a

remarkable continuity in military theory, and in this as well as in science and

technology North America is very much an extension of the European tradition.

By the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the USA was the

greatest military-technological power in the world, but already in the nineteenth

century Americans made contributions, for instance the popular revolver

invented by Samuel Colt (1814-1862) or the successful machine gun invented by

Richard Jordan Gatling (1818-1903).

George Washington (1732-1799), the first President of the United

States of America, possessed his own copy of De Re Militari (Concerning

Military Matters), a compendium of Roman military practice first composed

by Flavius Renatus Vegetius around the year AD 390 and revised into its final

form about fifty years later. It remained popular and studied throughout the

medieval and modern era. The same can be said about other classical works on

military affairs. In The Cambridge History of Warfare, Geoffrey Parker

writes:

âIn AD 1594 Maurice of Nassau and his cousins in the

Netherlands devised the crucial innovation of volley fire for muskets after

reading the account in Aelianâs Tactics (written c. AD 100) of the

techniques employed by the javelin- and sling-shot throwers of the Roman army,

and spent the next decade introducing to their troops the drills practised by

the legions. In the nineteenth century Napoleon III and Helmut von Moltke both

translated the campaign histories of Julius Caesar, written almost 2,000 years

earlier, while Count Alfred von Schlieffen and his successors in the Prussian

general staff expressly modelled their strategy for destroying France in the

ânext warâ upon the stunningly successful tactic of encirclement attributed

by Roman writers to Hannibal at the battle of Cannae in 216 BCâŚ.General

George C. Marshall argued that a soldier should begin his military education by

reading Thucydidesâ History of the Peloponnesian War, written almost

2,500 years before. These striking continuities derive from the fact that

ancient theorists and modern practitioners of war shared not only a love of

precedent, and a conviction that past examples could and should influence

present practice, but also a willingness to accept ideas from all quarters.â

Hannibal (247-ca. 183 BC) from the North African city of

Carthage with its Phoenician-derived culture is generally considered one of the

greatest military leaders of Antiquity. He was feared by contemporary Romans

and commanded the Carthaginian forces with great skill in the Second Punic War

(218-201 BC). The Italian Renaissance writer, civil servant and political

theorist Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527), known for his works Discourses on

Livy and especially The Prince, admired Hannibal as a military commander but was

otherwise heavily influenced by Roman examples. His âMachiavellianâ view of

politics as a practical discipline, based on empirical studies, is far removed

from Greek idealism.

The Punic Wars illustrate how ruthless the Romans could be

in dealing with potential threats. The statesman and orator Marcus Porcius Cato

(234-149 BC), better known as Cato the Elder, famously repeated the mantra Carthago

delenda est, âCarthage must be destroyed,â as often as he could. Carthage was destroyed

during the Third Punic War (149-146 BC). After this, Romeâs position as the

greatest political force in the Mediterranean world was uncontested.

Many bad things can be said about the Romans, who had

numerous flaws. However, the one flaw that they didnât have was

self-loathing. How would the ancient Romans in the mature phase of their

civilization have reacted to the threat posed by Islamic Jihad? I seriously

doubt that they would have blamed themselves for being attacked, as many modern

Westerners did after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 or the London

and Madrid

bombings. I also doubt whether they would have reacted with similar passivity

faced with the repeated gang rapes of their daughters by hostile aliens in

their cities. My bet is that faced with such Jihadist attacks, a prominent

member of the Roman Senate would now have been saying Mecca delenda est.

Fjordman is a noted Norwegian blogger who has written for many

conservative web sites. He used to have his own Fjordman Blog in the past, but

it is no longer active.

http://globalpolitician.com/print.asp?id=5605